Black and white high contrast photographic realistic of monumental made of cracking glass, realistic left and right hands and arms and head only, lying face down towards viewer, speaking with authority at viewer to the left, realistic fingers grasp rocks, high waves surround the rocks depicting a stormy scene with dark clouds sky, dramatic minimal lighting in sky, austere, evoking change, chaos, highly detailed.

Black-and-white high contrast photographic realistic of monumental made of cracking glass. realistic left and right hands and arms and head only, lying face down towards viewer, speaking with authority at viewer to the left, real five fingers grasp rocks, high waves surround the rocks depicting a stormy scene with dark cloudy sky, dramatic minimal lighting in sky, austere, evoking change, chaos, highly detailed.

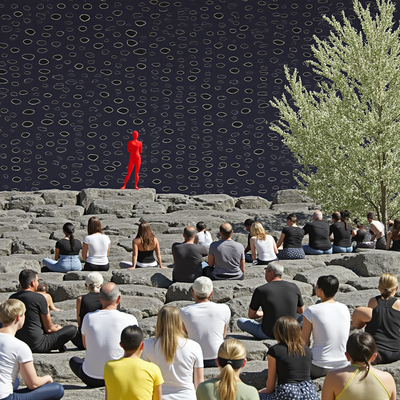

These two images represent the moment I felt there was something to show for my exploratory efforts! The top left was generated with the Flux.1-dev model. The lower left image from a library of 77 photographs collated in the previous research phase and trained with a custom-made model. The same prompt was used for both images.

Prompt editing included substituting ‘human’ – a deliberate word substitute for Satan to lessen AI’s stereotypical and monotonous interpretations – with ‘person’. This improved details like fingers and, in some instances, enhanced the androgynous representation I was hoping to achieve. The choice of ‘cracking glass’ to describe appearance was an attempt to challenge AI image generation skin tone bias. The abbreviation of ‘prdlst’ in the lower image prompt connects the prompt with extracts from Paradise Lost randomly selected and embedded in the descriptions of each photograph in the photo library.

Immersive Arts Explore funding allowed me to develop Paradise Unseen, my idea of linking extracts from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Book 1 to descriptions of photographs for the purpose of training an AI model to generate images. I wished to challenge the absence of disability representation in AI text‑to‑image generation and the ocularcentrism of art practice.

A huge leap forward, after months of trial and error, was the first time I saw a generated image that I had conceived of in my mind. Had I stumbled on a conceptual approach to AI image generation that fits with my way of photographing? Never presuming, always checking. I am not interested in developing or fine-tuning predetermined image styles. Instead of straining to see what was right before me, staring me in the face, I could include the word, ‘closeup’ in the prompt to influence a composition. This is how I photograph and rely on a 35mm camera lens to be physically close to my subjects. By substituting a word in a prompt, the results were unexpected, like the curious details produced with a flashlight in my light painting photography.

My interest in John Milton writing Paradise Lost after he lost his sight and the haptic quality of the verse, in combination with my myopic focus on extracts from Book 1, gave me a chance to consider a personal interpretation of the antihero and its contemporary relevance. And whether the poem’s Biblical and historic references to the meaning of a state of disobedience with its ensuing chaos have changed since the seventeenth century.

Commercial AI models are often trained on photographs without consent, whereas Paradise Unseen relied on voluntary submissions from disabled people and emphasised the respect of individual privacy. I worked with Ilia Pavlov, an AI engineer from the Creative Computing Institute, University of the Arts, London. We share a mutual concern about the lack of information and understanding of ‘Black Box AI’ – what influences a base model, and how these impact Low Rank Adapter (LoRA) training.

Explore a series of links to 8 boards showing the progress made in my Immersive Arts funded project to explore Al bias and image generation. Click on the images below to view the boards.

23/07–03/08/2025

We know the inputs and outputs, yet the inner workings of this “black box” remain unknown.

Voluntary submissions were not enough to train the model. It was impractical perhaps to address within the project’s limited timeframe the logistics of anticipating disabled artists would respond to my request. Even though I contacted disability arts organisations and others supporting disabled people and their families. Also, I promoted the photo callout through a series of social media posts. The interest from the contacts I did make during this time is reassuring. I intend building on these relationships, sharing what I have learnt so far, and requesting consent for me to photograph people with disabilities interested in being included in my photo library for the model training. This more personal approach, albeit slower, is key to the way I work as a visually impaired photographer.

The interest in Paradise Unseen on LinkedIn and Instagram from the academic community and from accessibility consultants gave me confidence to see that I am contributing to public discussion and awareness of disability representation in AI image generation. I welcome enquiries from organisations and individuals interested in challenging the absence of disability representation in AI-generated images, and the ocularcentrism of art practice.

I am planning an experimental phase of Paradise Unseen where I may be able to share what I have learnt. This includes honing my skills of prompt writing using audio description techniques to address diversity representation in image generation. I intend working with Ilia, the AI engineer, in the development and facilitation of a creative AI image generation online training workshop series for disabled artists. My wish is to collaborate with a small cohort of disabled artists (2–4) interested in implementing AI image generation in their creative practice. And for us to have an opportunity to share our joint creative outcomes with community arts organisations to raise awareness of the critical approach to AI image generation that is emerging from Paradise Unseen. A new challenge, and one I welcome, would be to promote this project as it develops by teaming up with interested social media creators on a pre-planned social media campaign.

Thank you very much to the following: Immersive Arts for their Explore funding and Producer, Michelle Rumney for her encouragement. Engineer, Ilia Pavlov for the planning and development of a LoRA and generous sharing of his knowledge. Matthew Cock for his belief in what I am trying to achieve. Wojciech Wolocznik for his support and patience. Tom Godfrey, Director of Bonington Gallery, Nottingham Trent University and Professor Hugh Adlington, Department of English Literature, University of Birmingham, a Milton scholar, I appreciate both your continued interest. Margaret Visser, you inspire me daily.

Paradise Unseen is dedicated to photographer and curator Douglas McCulloh, who sadly died in January 2025.

An Access to Work grant from Department of Work and Pensions supported the design of this webpage.

© Karren Visser. Paradise Unseen, funded by Immersive Arts UK, 2025.